A Letter to Mama

A Letter to Mama

By Isaac Bashevis Singer

JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS - Spring 2019

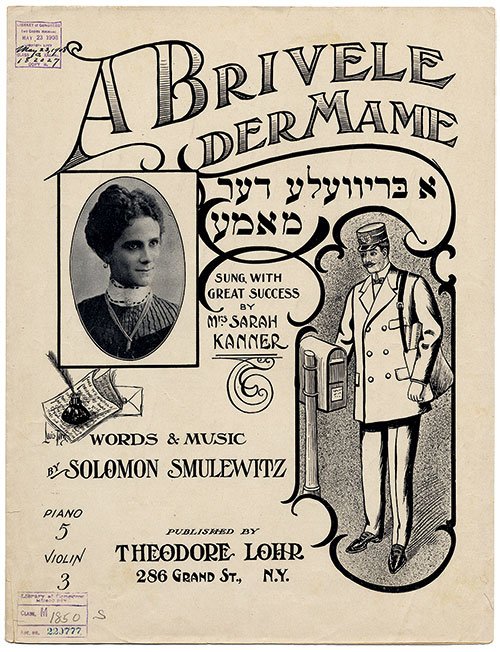

The cover of the music score for “A brivele der mame,” 1907. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress Music Division.)

In “A Letter to Mama,” which appears here for the first time in English, Isaac Bashevis Singer tells the story of Sam Metzger, who, having immigrated to America, marries and establishes a successful clothing shop with his wife, Bessie, without ever writing home to his widowed mother in Poland. Now almost 60, unhappy in his marriage and estranged from his daughter, he is overwhelmed by the enormity of his neglect of his mother in Poland and his abandonment of Yiddishkeit. “In his effort to forget,” Singer writes, “Sam had become a traitor to his people.”

Singer’s postwar fiction about America was generally set in the contemporaneous present, describing the new American lives of refugees and survivors of the Holocaust. “A Letter to Mama,” which was originally published in the Forverts on October 29, 1965, is something of an exception. Its mention of Hitler’s threats to invade Poland and the vivid description of the Yiddish literary scene in the Café Royal clearly place it in the late 1930s, and yet other details and cultural markers have an anachronistic feel. For instance, the Metzgers’ comfortable house in a small Illinois town is described as being a “$60,000 home,” but in the late 1930s, $60,000 would have bought a mansion in the Midwest. Less definitively, Sam’s daughter Sylvia goes to school in California, is engaged to a non-Jew, and admits to her mother that she has had an abortion, all of which certainly could have happened in the 1930s, but would be more culturally typical of the mid-1960s when Singer wrote the story. Perhaps these somewhat incongruous details are meant to underline its dreamlike atmosphere.

The most powerful cultural reference is in the story’s title. The song, “A brivele der mamen” (A Letter to Mama), was composed by Solomon Shmulewitz in 1907, and tells the story of a young man who immigrates to America, finds success, but ignores his mother back in the Old Country—until one day he receives a letter saying that his mother has died and that her last wish was for him to say Kaddish for her. More haunting than the reference itself, which Singer would have expected his Yiddish readers to recognize instantly, is the fact that the song eventually inspired a film of the same name, which was one of the last Yiddish films to have been produced in Poland, in 1938. It opened to packed theaters in New York the following year at more or less the moment in which the story is set. With a single stroke, Singer evokes not only the difficult experience of separation caused by emigration from Poland, but also the finality of that separation for those who found themselves on the other side of the Atlantic with the outbreak of the Second World War.