News

The latest news and events about Isaac Bashevis Singer.

“I’m sometime afraid that men will get to the conclusion that reading fiction is a waist of time…”

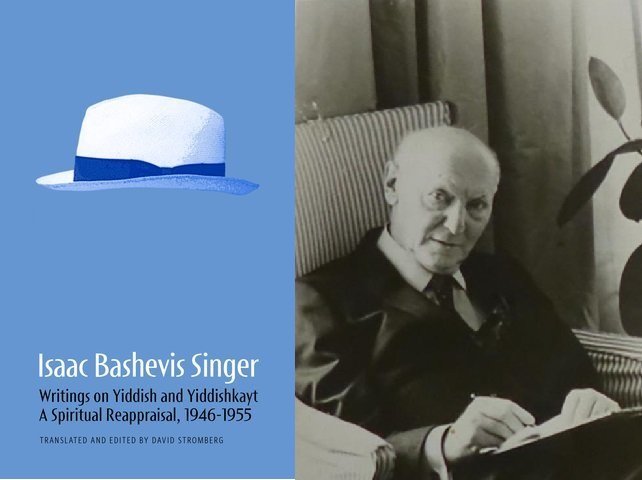

WRITINGS ON YIDDISH AND YIDDISHKAYT - A SPIRITUAL REAPPRAISAL, 1946-1955

A well-crafted anthology of musings from a giant of Jewish literature.

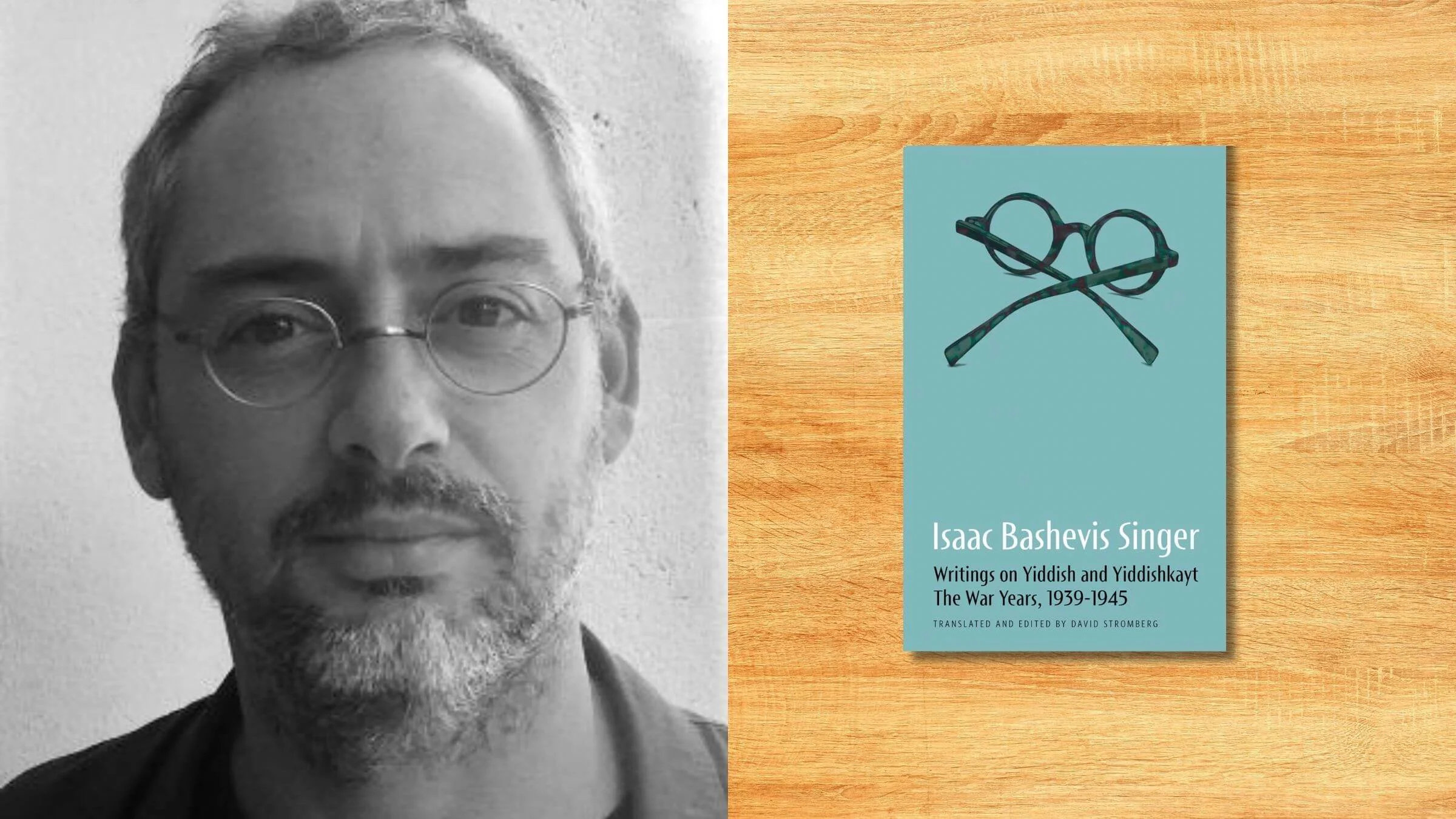

Isaac Bashevis Singer: Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt Volume 2A Spiritual Reappraisal, 1946-1955 - Literary scholar David Stromberg discusses the astonishing career of the eminent Yiddish-language author, Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Now Bashevis’s Demons, direct from engagements in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, has arrived at Off Broadway’s Theatre 154 comprised of three short stories in the original Yiddish with English supertitles as a fascinating combination of both Story Theater and a dramatic reading.

Bashevis’ Demons, an evening of three staged Singer stories, is playing at Theatre 154 in the West Village. Starring Shane Baker and Miriyem-Khaye Seigel, the show played Buenos Aires, Stockholm and Rio De Janeiro before arriving in Singer’s adopted home of New York

Stromberg offers newly translated essays by Nobel laurate Isaac Bashevis Singer that shed light on the Polish American author’s postwar transformation.

Bashevis's Demons by Isaac Bashevis Singer

Dec 18 2024 through Jan 5 2025

Theatre 154 (154 Christopher Street)

Bashevis's Demons by Isaac Bashevis Singer

Dec 18 2024 through Jan 5 2025

Theatre 154 (154 Christopher Street)

“Prepare to be astonished” The Age

Yentl is an ode to the feminist undertones and queer subtext of the original story and an invitation to celebrate the beauty of Yiddish culture.

Sometimes a publisher gets lucky. The publisher works to bring out a book of historical interest that seems to have a modest potential readership, and then events make that book suddenly widely relevant.

Compared to his fiction, Singer’s work as a journalist often gets short shrift. But translator David Stromberg argues that the writer’s output as a newspaper contributor is inseparable from his later books.

The expression “Don’t get me wrong” is a good place to start – an ethical mandate as well as a critic’s dictum.

In 1966, the critic Irving Howe published an essay whose title, “The Other Singer,” testified to a literary usurpation. For American readers in the nineteen-sixties, the name Singer meant Isaac Bashevis Singer. In Howe’s opinion, however, the ascent of I. B. Singer—known to Yiddish readers by his nom de plume, Bashevis—was not a cause for celebration, because it meant the eclipse of a better writer: his older brother, Israel Joshua Singer.

Perhaps a modicum of perspective could be provided by cracking it open and reading Singer’s reactions as news of Nazi atrocities in Europe reached the United States, his new home.

Isaac Bashevis Singer, edited and trans. from the Yiddish by David Stromberg. White Goat, $24.95. Isaac Bashevis Singer originally published each of these pieces under pseudonyms in Forverts, the world's oldest Yiddish newspaper, when he was still relatively unknown. The essays are arranged chronologically, offering readers the unique opportunity to bear witness to the shifts in Singer's perspective as history unfolded

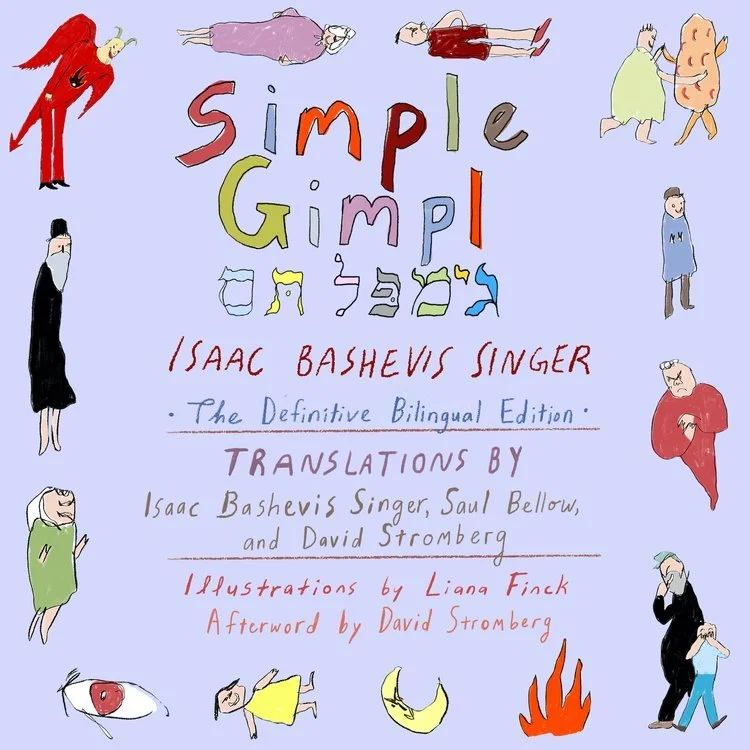

The story, originally “Gimpl tam” in Yiddish, is familiar to English readers as “Gimpel the Fool,” the title Saul Bellow used for his famous 1953 translation. The new, definitive edition contains Singer’s original Yiddish text together with Bellow’s version, alongside a new translation by David Stromberg

Beautifully printed and presented, this new edition is a gift to readers and scholars alike.

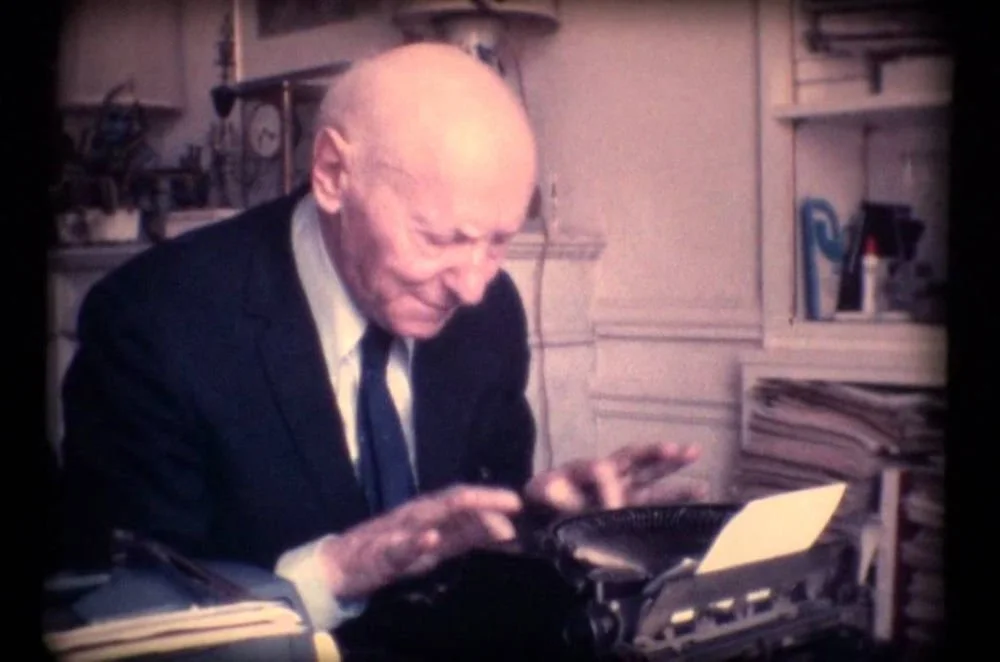

Looking back on my life, I can remember always being exceedingly curious about the unusual, the mysterious, the miraculous.

This faith in individual human stories was the reason Singer chose to write in Yiddish rather than Hebrew. In Jewish Eastern Europe, Yiddish was the language of everyday life, but it was traditionally held in low esteem by the learned elite, who wrote their books in the sacred tongue of Hebrew.

Artists, like plants, must have roots, and the deeper the soil, the deeper the roots. Singer recognized that much of contemporary literature was neither new in spirit nor style. In an attempt to be politically correct in accordance with the times, it was banal and had simply dressed up old clichés in “red clothing.”

Who needs Yiddish? It turns out that everybody does. While the essays in this volume on the whole do not match Singer’s fiction at its best, together they provide an invaluable supplement to our understanding of this extraordinary writer’s vision.

The collection of papers of Isaac Bashevis Singer includes handwritten drafts of his writings in Yiddish as well as English translations filled with his own revisions, and it’s full of treasures still to be shared with the world.

One little moment like that — you say, “Hmm, I wonder what that refers to” — can lead to 10 years of research. And you have to grab onto those moments. Those are extremely important moments.

Old Truths and New Clichés brims with stunning archival finds that will make a significant impact on how readers understand Singer and his work. Singer's critical essays have long been overlooked because he has been thought of almost exclusively as a storyteller.

“It could be said that Hebrew succeeded and Yiddish failed, but for me Yiddish is far from being a failure”

From “Journalism and Literature,” an essay that appears for the first time in English in the collection Old Truths and New Clichés, which will be published next month by Princeton University Press.