This faith in individual human stories was the reason Singer chose to write in Yiddish rather than Hebrew. In Jewish Eastern Europe, Yiddish was the language of everyday life, but it was traditionally held in low esteem by the learned elite, who wrote their books in the sacred tongue of Hebrew.

Read MoreNews & Events

Check here for the latest news about upcoming events, and insights into Singer's life, work, and historical legacy.

Artists, like plants, must have roots, and the deeper the soil, the deeper the roots. Singer recognized that much of contemporary literature was neither new in spirit nor style. In an attempt to be politically correct in accordance with the times, it was banal and had simply dressed up old clichés in “red clothing.”

Read MoreWho needs Yiddish? It turns out that everybody does. While the essays in this volume on the whole do not match Singer’s fiction at its best, together they provide an invaluable supplement to our understanding of this extraordinary writer’s vision.

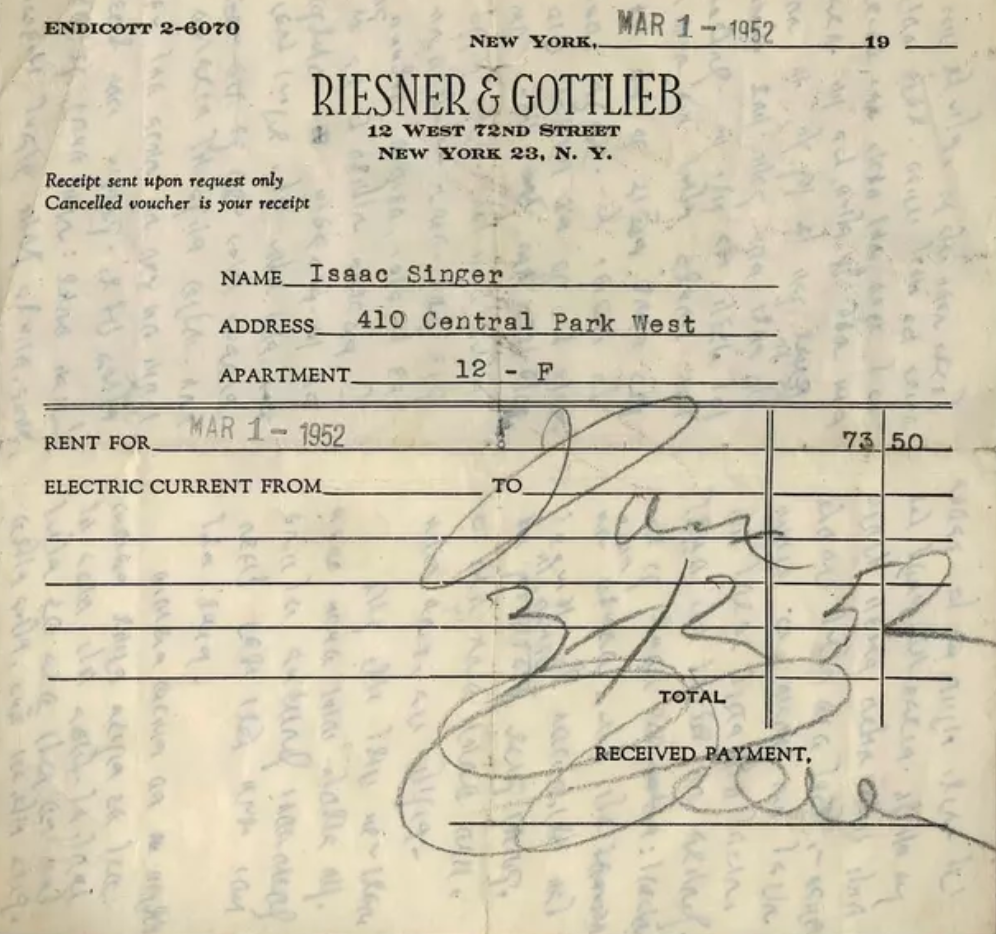

Read MoreThe collection of papers of Isaac Bashevis Singer includes handwritten drafts of his writings in Yiddish as well as English translations filled with his own revisions, and it’s full of treasures still to be shared with the world.

One little moment like that — you say, “Hmm, I wonder what that refers to” — can lead to 10 years of research. And you have to grab onto those moments. Those are extremely important moments.

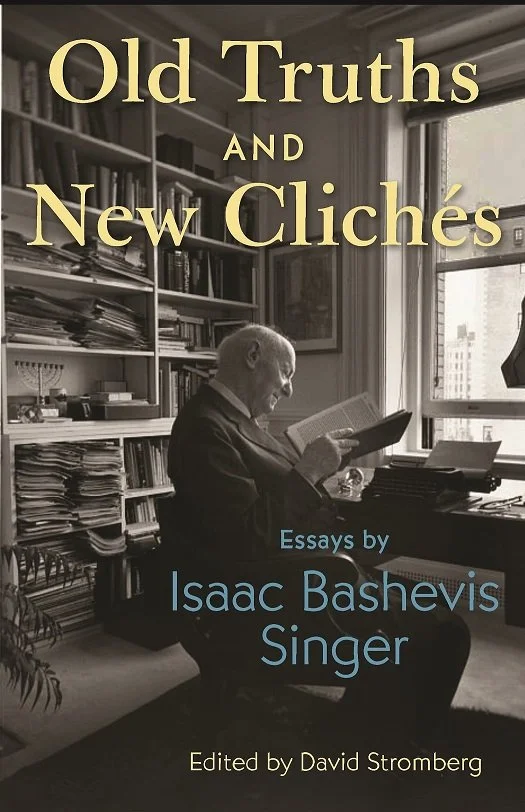

Old Truths and New Clichés brims with stunning archival finds that will make a significant impact on how readers understand Singer and his work. Singer's critical essays have long been overlooked because he has been thought of almost exclusively as a storyteller.

“It could be said that Hebrew succeeded and Yiddish failed, but for me Yiddish is far from being a failure”

From “Journalism and Literature,” an essay that appears for the first time in English in the collection Old Truths and New Clichés, which will be published next month by Princeton University Press.

Read MoreTranslator Stromberg (Baddies) brings together 19 essays by Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer (1902–1991) in this touching collection.

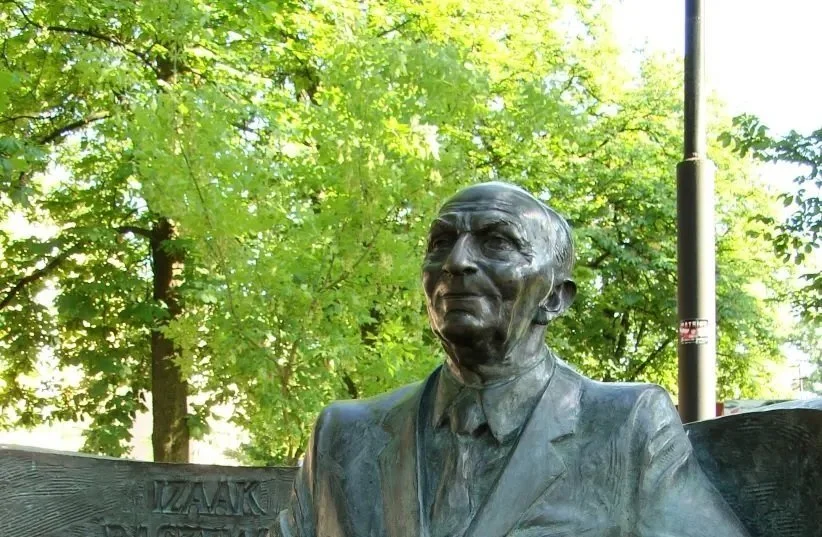

Read MoreWhen Isaac Bashevis Singer passed away in 1991, he knew that his work would be left undone. He had left behind heaps and piles of material in his so-called “chaos room” – the walk-in closet where he kept manuscripts, clippings, notebooks, certificates, diplomas, awards, letters, and many other documents and objects from his literary and personal life.

Read MoreOn the bed lay a small man, stark naked, with a little black beard and gray in the middle. His high sunburned forehead was pink and peeling.

Read MoreFor some time now, people have spoken of Yiddish and Hebrew coming closer together. It’s hard to understand what exactly this “closer together” is supposed to be about—or what it should allow us to do.

Read MoreThis warm-hearted comic romance tells the story of hapless teenager David Bendiger, who washes up penniless in 1922 Warsaw.

Read MoreThe New York Times called Isaac Bashevis Singer a Polish writer. Here’s how Wikipedia warriors made him Jewish again.

Read MoreIsaac Bashevis Singer’s first literary venture was lost for almost a century—until a partial copy resurfaced in an attic in Poland.

Read MoreA searingly personal, deeply moving prayer is discovered in the Nobel Laureate’s papers.

Read MoreAlmost all of Singer’s stories were first published in Yiddish, most often in The Jewish Daily Forward, the Yiddish newspaper for which Singer worked. “On a Ship” is a rare exception. Believed to be written sometime in the late 1960s or early 1970s, the story was sent to us by David Stromberg, the editor of Singer’s estate. He found the story — translated to English and in handwritten fragments in Yiddish — while going through Singer’s vast archives. This is its first publication in any language. It was translated from the Yiddish by the author and Nancy Gerstein.

Read MoreIsaac Bashevis Singer’s earliest Chelm stories appeared in English as part of his first collection for children, Zlateh the Goat (1966), illustrated by Maurice Sendak, who was then already known as an author and illustrator of children's literature.

Read More